Douglas Gerrard on how Indonesia’s genocidal occupation of West Papua is written out of history.

Douglas Gerrard22 November 2024

From 1935 to 1936, Mohammad Hatta was interned in Boven Digoel, a Dutch concentration camp for Indonesian communists and nationalists in modern-day West Papua. Together with Sutan Sjahrir, another key figure in the pro-independence organisation Perhimpunan Indonesia, Hatta was the victim of an obstinate colonial policy that refused to brook any compromise with the native desire for freedom. Here, deep in the New Guinea rainforest, Indonesia’s future leaders played football, fought dysentery and malaria, and watched as their fellow inmates made periodic and doomed escape attempts.

Eventually released into the tumult of World War II, Hatta forged an alliance with the occupying Japanese, gambling (correctly) that their policy of ‘anti-colonial fascism’ would allow the Indonesian Revolusi to progress. In August 1945, with Japan in retreat, Hatta and his fellow revolutionary Sukarno signed the Proklamasi, the Indonesian declaration of independence. They were to become Indonesia’s first vice-President and President respectively. Hatta’s campmate Sjahrir was appointed Prime Minister.

From there, the Revolusi became an extremely bloody war, as the Dutch used brutal violence to try and regain authority over an ever-shifting landscape of control. For much of this period the Netherlands had the upper hand militarily, but their hopes of reclaiming the bulk of their former territory were ended by US intervention in 1948. Fearful of Indonesia slipping under Soviet influence – and encouraged by the ruthlessness with which Sukarno had crushed a communist revolt in East Java – the US warned that further Dutch military action would come at the cost of Marshall aid and NATO support. Chastened, the Netherlands withdrew in December 1949. Indonesia had won political independence. Finally, the Revolusi travelled to Bandung, where the newly-liberated nations of the Third World gathered to herald the end of colonialism. From Boven Digoel and subjection to Bandung and liberation: so the Indonesian revolution gave ‘birth to the modern world’, as the subtitle of David Van Reybrouck’s landmark new history, Revolusi, suggests.

Despite its central place in Indonesian history, Van Reybrouck does not appear to have visited Boven Digoel as part of his fieldwork. Had he done so, he would have found a rapidly clearing landscape much different from the ‘impenetrable’ forest that surrounded the camp. The area around the Digoel river is now home to the agribusiness project, Tanah Merah, set to become the largest single palm oil plantation on earth.

Already home to the world’s largest gold mine, West Papua – the Western half of the island of New Guinea – provided around 40% of Indonesia’s GDP during Suharto’s New Order dictatorship. Outgoing Indonesian President Joko Widodo has renewed this dependence, supervising the construction or expansion of numerous industrial mega-projects. Tanah Merah is a key node in Indonesia’s green transition, which manifests in its Papuan periphery as a form of climate colonialism. As it hauls itself towards food security and energy independence, Indonesia is increasingly trading dirty coal for West Papuan gas and biofuel, hoping to finance the shortfall partly through Papuan gold and ‘sustainable’ Papuan palm oil.

That West Papua’s place in the world order is unknown is due, at least in part, to widespread ignorance of its Indonesian occupier. Early on in Revolusi, Van Reybrouck quotes in exasperation a classic expat joke: ‘Any idea where Indonesia is?’ ‘Not really – somewhere near Bali?’. His point is apt. Indonesia is the world’s fourth largest country, hosting its largest Muslim population; its biggest palm oil producer; a pre-eminent exporter of critical resources, including rubber, tin, and coal; a vast archipelago marking the strategic hinge point between Asia and the Pacific – and yet many Westerners would struggle to place it on a map.

Revolusi represents a welcome corrective to such obliviousness. Van Reybrouck sets out to vindicate the Indonesian revolution, reinstating Indonesia’s subaltern classes as a historical actor through hundreds of interviews with its participants. But incomplete testimony furnishes incomplete history. In common with other recent histories of Indonesia, such as Max Lane’s Unfinished Nation or Vincent Bevins’ The Jakarta Method, Van Reybrouck excludes West Papuans and their national struggle from his narrative. In so doing, such works ensure that the most critical years of West Papuan history are told entirely from the colonisers’ perspective. In this sense, Revolusi is at once an important study of an often-forgotten history, and itself an act of forgetting, a snapshot of an ongoing process of erasure which helps keep Indonesia’s occupation of West Papua from international attention.

Against this process of erasure, we should aim to assist the West Papuan struggle by putting West Papua back into history – a project that can begin by revisiting the Bandung Conference.

For the left, Bandung appears as a glimpse into a lost future – an alternative postimperial order ultimately smothered by US intervention – and a mobilising cry for renewed South-South cooperation and solidarity. Yet it is largely forgotten that one of Indonesia’s key motivations for hosting the Conference was to press its claim to West Papua, particularly to sceptical African nations.

The uncertain status of West Papua – the one territory the Netherlands had refused to relinquish in 1949 – had set liberated Indonesia on a renewed collision course with its former coloniser. Bandung was therefore both an explosive reckoning with colonialism, and a middle chapter of the ‘New Guinea dispute’, the thirteen years of political wrangling over West Papua that followed Indonesian independence.

Most histories, Revolusi included, present this as a binary conflict: Indonesia fighting to complete its national revolution, the Netherlands seeking a colonial bridgehead as they retreated from the East. In actuality, the dispute was three-sided, with West Papuans caught between competing colonialisms.

Dutch ambitions were scaled up and down according to the geopolitical reality. An initial plan to retain West Papua as a colonial halfway house for hundreds of thousands of displaced Indies Dutch eventually gave way, again under US pressure, to cynical support for West Papuan self-determination. Though motivated by revanchism, Dutch patronage was hardly likely to be declined by West Papuans whose avenues for significant Third World support had largely been closed at Bandung.

For Sukarno, West Papua was an obsession. He called for the ‘total mobilisation of the Indonesian people’, nationalised private Dutch assets, and led demonstrations in chants of ‘from Sabang to Merauke!’ (marking Indonesia’s westernmost and easternmost points, in Aceh and Papua respectively). Would West Papua have seemed so pivotal to the revolution without his fixation? That Indonesia’s beloved founding father was also the chief proponent of re-colonisation cannot be ignored. Hatta, for instance, was markedly less enthusiastic about a drawn-out Papuan campaign, and even argued for West Papuan self-determination on the basis of its ethnic and cultural difference. Furthermore, in the years following Bandung, Sukarno cast West Papuans in uncomfortably racialised terms, as either Stone Age peoples unready for self-governance, or imperial puppets threatening to establish a Dutch vassal state.

Under growing pressure from his left and right flanks, recovering West Papua served for Sukarno a strategic goal as well as an ideological one, acting as a means of holding together a disparate revolutionary coalition.

There remained various objective impediments to his plan. For one thing, Papuans lacked a shared history of colonisation with the rest of the archipelago. To be sure, West Papua was officially Dutch territory, and Papuans had also resisted Dutch colonialism. From 1938 to 1942, a Biak priestess named Angganita Menufandu led the anti-imperialist Koreri movement, which flouted the prohibitions on indigenous dances and encouraged mass non-cooperation with colonial law. In general, however, the Dutch were not so interested in mastering the Papuan interior. The heavy rain and mountainous terrain stunted any grand agricultural designs, while the vast mineral wealth beneath the topsoil had not yet been discovered. Instead, parts of the coasts were cultivated for trade, while missionaries gradually brought Christianity to the highlands.

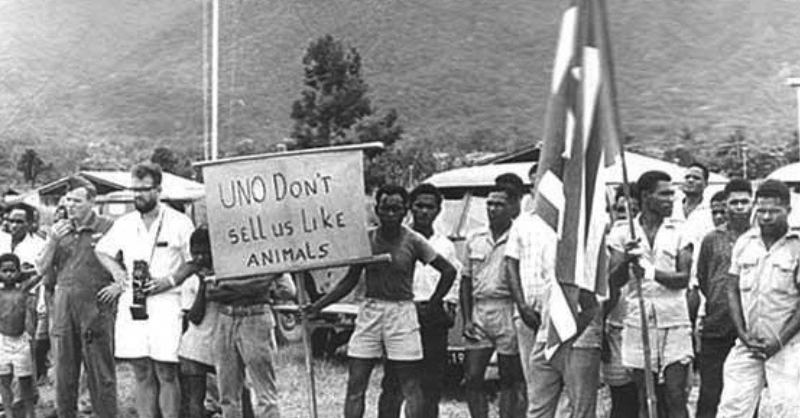

As such, Indonesia’s initial takeover of West Papua in the early 1960s represented the first real experience of foreign rule for a majority of the population. A second critical factor was the emergence and spread of West Papuan nationalism: belying Sukarno’s claims of Dutch puppetry, the contours of a free West Papua had been drawn long before he set out to ‘liberate’ the territory. Angganita had called for the expulsion of the Dutch and their Indonesian middlemen, and anticipated an independent West Papua ‘from Sorong to Merauke’; prefiguring Sukarno’s formulation, but marking the borders of Dutch New Guinea. Koreri also inverted the Dutch tricolour and added the sacred Morning Star, providing the blueprint for the West Papuan national flag, now banned under Indonesian rule. In 1961, the Morning Star flag was raised across West Papua for the first time, and the New Guinea Council declared independence, ‘in accordance with the ardent desire and the yearning of our people’.

Just as West Papuan nationalism was reaching maturation, however, the geopolitical balance was tilting in the other direction. Once again anxious about Indonesia going communist, the US forced the Netherlands to back down. After more than a decade of diplomatic and military manoeuvring, Sukarno had finally won unambiguous American – and UN – backing for his Papuan ambitions.

Here, Revolusi again shows how West Papua can be hidden in its own history, as Van Reybrouck describes what followed in curiously neutral terms: ‘In 1962 the territory was placed under UN control. Six months later it was the Republic’s’. Concealed within this innocent formulation are the three foundational betrayals of the West Papuan nation: first, the 1962 New York Agreement, the mechanism by which West Papua was ‘placed under UN control’. Signed between the Netherlands, Indonesia, and the US, the Agreement stipulated that the Dutch immediately transfer control of West Papua to the UN, who would then hand administration over to Indonesia in increments. If West Papua is Indonesia’s Palestine, then New York was its Balfour Declaration, with Papuans shut out of the negotiations that signed away their land.

Betrayal two was the Act of Free Choice, known to West Papuans as the ‘Act of No Choice’. The Act was ostensibly a provision for West Papuan freedom: under the terms of the New York Agreement, Indonesia was instructed to hold a self-determination referendum by 1969. However, by the mid-1960s Indonesia was at war with the Organisasi Papua Merdeka (Free Papua Movement), which a contemporary US State Department communique recognised as an ‘all-pervasive revolutionary movement’. The Indonesian government had also signed a contract with mining giant Freeport McMoran to cultivate the world’s largest gold deposit in the Mimika highlands. Gambling such a bounty on a losing referendum was unthinkable. Accordingly, Indonesian officials hand-picked 1,026 Papuan elders – around 0.1% of the indigenous population – and forced them at gunpoint to vote against independence. The UN then obediently rubber stamped this flagrant violation of international law – no doubt reassured by US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger’s assertion that an election ‘would be almost meaningless among the stone-age cultures of New Guinea’.

The final historical elision concerns the material process by which Indonesia took possession of West Papua. Van Reybrouck’s version – ‘six month’s later it was the Republic’s’ – suggests a frictionless administrative handover: the Dutch tricolour is lowered over a government building and the Indonesian flag raised in its place. What in fact transpired was a fully-fledged military invasion. Indonesian paratroopers, already dropped into strategic locations across the territory, were reconstituted into a military division under the command of future dictator General Suharto. West Papuan nationalists were imprisoned and tortured.

The rudimentary state apparatus that had been constructed under Dutch supervision was immediately dismantled: all political parties were dissolved, elections were banned, and the indigenous Papuan Volunteer Corps disarmed. A cautious Papuanisation of the civil service had taken place in the 1950s, another result of the Dutch sensing the winds of change. This too was rapidly undone, with politically suspect Papuans replaced by Javanese settlers – presaging the World Bank-sponsored transmigration programmes, undertaken from the 1970s onwards, which have made indigenous Papuans a minority in their own lands.

Having liberated West Papuan territory, Indonesia set about liberating West Papuan minds. Thousands of Papuans were forced to watch as masses of indigenous artefacts and Morning Star flags were thrown into a huge bonfire, in a symbolic extinguishment of their ‘colonial’ identities. The aim, in the words of Foreign Minister Subandrio, was to ‘get [Papuans] down out of the trees’. The beginning of Indonesian occupation was thus suffused with racist and hierarchical notions familiar from European colonialism.

However, there was a crucial difference: West Papuans experienced Dutch racism primarily as paternalism, which first patronised their governing capacities, and then promised to teach them statehood. Indonesia refashioned colonial racism into a weapon that could crush a free West Papua. The myth of the primeval Papuan continues to animate Indonesia’s approach to the occupation today: the 2019 West Papuan uprising, the largest pro-independence protest for a generation, was set in motion by the racist abuse of a group of Papuan students by Indonesian police.

This edited collection celebrates Patrick Wolfe’s contribution to the study and critique of settler colonialism as a distinct mode of domination. The chapters collected here focus on the settler-co… Paperback

We are sorry this title is currently out of stock in your selected territory. Please check back or contact us for more information.

How, then, to assess West Papuan history against this revised chronology? Complicating nostalgic narratives of Bandung, it is clear that the Revolusi’s final chapter simply was the colonisation of West Papua; to ignore this is to engage the same epistemic imperialism that sees the history of colonised peoples as simply the history of the colonisers. Just as West Papuans were excluded from the New York Agreement and Act of Free Choice, so too are they frequently written out of their own history.

By concealing the critical impact of these years on the continued violation of West Papuan self-determination, writers like Van Reybrouck inadvertently collude with Indonesia in its own Papuan vanishing trick. West Papua is one of the world’s least free societies: foreign journalists are banned, along with international NGOs and human rights groups. Remarkably, Indonesia also continues to refuse access to the UN (in this respect, Widodo has proven more intransigent than Xi Jingping, who invited the UN to report from Uyghur Xinjiang in 2022). West Papua remains an authoritarian enclave within a semi-democratic state, retaining much of the architecture of the New Order – chiefly the autonomous power of the Indonesian military, which operates with functional impunity and supplements its income through corporate protection rackets.

This Papuan blind spot is all the more nettling given the bloody realities of Indonesian rule. Contemporary West Papua is unmistakably a settler colony, where state building has been driven for decades by the interlocking strategies of territorial consolidation and resource extraction. Mimicking America’s taming of the Western frontier, Indonesia has settled hundreds of thousands of loyal Javanese throughout West Papua: often peasant farmers enticed by the promise of free land, but also a middle layer of administrators to staff the government, education and legal systems.

As Lachlan McNamee has shown, Indonesian transmigration programmes have specifically targeted restive border regions on the one hand, and mineral-rich hotspots like the Grasberg mine – containing the world’s largest gold deposits – on the other. One result is a profound ‘Javanisation’ of urban areas, which are now two-tiered spaces, visibly dominated by settlers, where Papuan culture is suffocated and political activity closely surveiled.

If the cities are effectively colonial encampments, rural West Papua, home to fewer transmigrants, more soldiers, and more intense resistance, is subjected to the worst violence. Analyses of Indonesian rule often employ the metaphor of a ‘slow-motion’ or ‘cold’ genocide to capture the daily abrasions of occupation; steady demographic dilution, land grabs, marginalisation and dispossession, punctuated by sporadic killings. It is true that the quotidian drudgery of occupation is more consequential than the atrocities that occasionally find their way into Western media coverage.

And yet West Papuans have been frequently subjected to spectacular – and largely unknown – episodes of mass violence, such as the 1977-78 killing of thousands in the Baliem Valley, the 1981 massacre of 13,000 in Paniai, or the 2021 decimation of entire villages in the Kiwirok border region. Estimates of the number killed range from 100,000 to 550,000, meaning that up to a quarter of West Papuans have lost their lives under Indonesian occupation. Genocide in West Papua has blown hot and cold.

While popular work on Indonesia tends to erase West Papua, there also exists a concomitant process of construction, transmitted through persistent tropes of backwardness, remoteness, and animality. Thus lurid articles fixate on poorly evidenced claims of tribal cannibalism, travel companies offer guided tours of ‘prehistoric’ tribes, and journalists reduce a complex episode in a liberation struggle to a ‘lawless’ land and ‘psychopath’ kidnappers.

ULTRA-SUPER-NATURAL, a Czech photography exhibition recently displayed in London, contrasts West Papuans in traditional clothes with images of astronauts and motifs of space travel. ‘We’ve watched these people on their journey from a Stone Age way of living into the digital age’, the artists state in their exhibition notes. Erasure and construction orbit one another, working both to shield what is seen of West Papua (custom, jungle, tribal warriors) from what is not (occupation, genocide, organised struggle).

Though mostly obscuring Papuans from view, at times Van Reybrouck is also guilty of a racialised orientalism. He writes of ‘primeval’ forest, ‘deathly silent and stiflingly hot, riddled with malarial mosquitoes, leeches, and crocodiles’. Here, trapped in this ‘far corner of the world’, he finds ‘naked, painted Papuans clamouring for tobacco’, ‘living out the Neolithic way of life they had preserved for millennia’.

Tracey Banivanua-Mar has described how such imagery works to naturalise West Papuans’ continued subjugation, placing them outside of time, let alone modernity, and thus squarely in the bulldozers’ path. Stone Age man is not a political actor. Notions of backwardness and savagery – described by Banivanua-Mar as the ‘silencing chatter of cannibals’ – serve to mask the actual violence of the Indonesian state, dealt out in the service of a merciless modernising project that sees West Papua as Indonesia’s ‘breadbasket’.

Of course, for West Papuans, the forest is a home, not a prison. The West Papuan liberation movement hopes it will furnish a future ‘Green State’, which it has made a central plank of its offer to the world. It’s a sensible strategy: climate catastrophe dictates that we all have an interest in protecting the New Guinea rainforest. With formerly verdant Sumatra and Kalimantan largely ‘logged out’, Indonesia is likely to rely increasingly on New Guinea for its subsistence.

One of Widodo’s last acts as President was to break ground on the largest industrial project ever devised (in West Papua, superlatives abound): a network of sugarcane and bioethanol concessions spanning an area the size of Wales. A correspondent military escalation is already underway, with 5000 additional soldiers having been deployed to Southeastern West Papua, where they will protect the sugar fields and processing mills from guerilla sabotage. Surveying the modernity the Revolusi helped build, it is impossible to see West Papua as anything less than climate change’s forgotten frontline. That we continue to ignore it is not only an historical or ethical failing, but a grave political mistake.

Douglas Gerrard is a writer and researcher based in London